Why are bonded curves interesting? Deep down, I think it’s because they allow us to write code that not only organizes information, but also specifies who benefits from organising it in different ways. Using a curve to model fluctuating supply/demand is exactly what it means to program money such that it can respond to its own role in markets.

Think about this: the medium (money) now has the linguistic capacity to reflect upon the mechanism by which its value is arrived at (a market) and adapt itself so as to incentivise human goals. The potential for feedback loops between code, economics and psychology are endless.

Cui Bono

Who benefits from organising the information you see is one of the biggest problems online today. Google has done a fairly good job, all things considered, yet:

- A corporation - that is, a legal fiction - benefits most. This corporation must then encourage its employees: “Don’t be evil”, rather than constructing systems that prevent corruption, as this is genuinely difficult and not always in its best interests.

- We are therefore inundated with #FakeNews, because there are no clear metrics by which to separate one human’s truth from another’s fallacy. Strong economic signals do not solve this, but they do introduce game theory into sharing information we think is valuable, and add a level of unprecedented transparency into how “relevance” or “weight” is calculated.

Early emissaries of the real promise of computing like Doug Engelbart envisioned networked machines as “augmented cyclical systems” that would allow us to navigate the stored knowledge of humanity collaboratively, and therefore more efficiently. This vision for collaboration was profound, but the problem is that you need to be able to define explicitly, i.e. in turns of economic value, the incentives for working together before people can collaborate productively.

Programmable money that is not only decentralised, but which can respond to its own role in the markets on which it is traded, is the chicken-egg we need to bootstrap incentive schemes at the scales required for global collaboration and organisation.

Design Space

The other exciting thing about this specific way of programming money is that the design space is literally huge. I won’t rehash others work, instead I want to explore a pleasant synchronicity that showcases the different ways in which bonded curves can be used in reality.

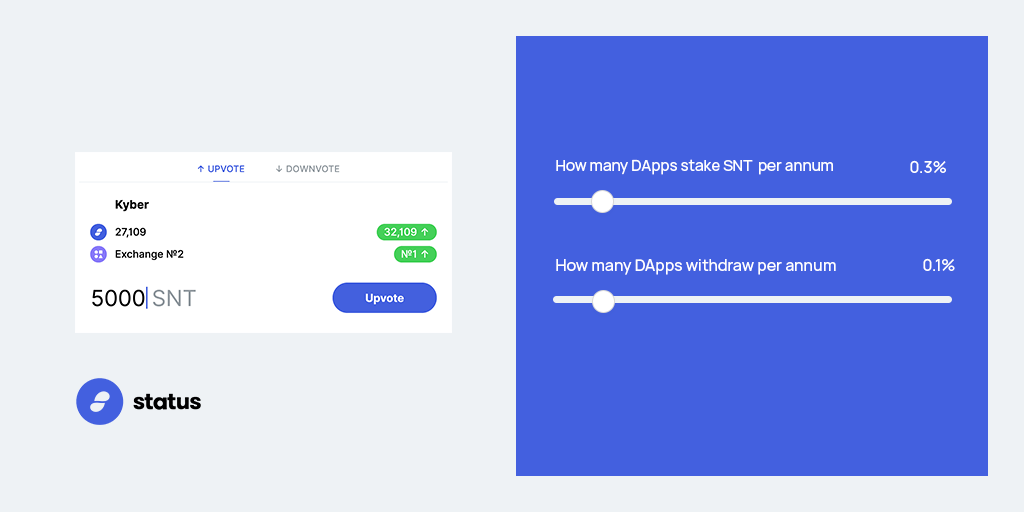

Discover curates and ranks DApps through various filters; we’ll just focus on the economic one here. The DApp that stakes most ranks highest; but the more you stake, the cheaper it is for the community to downvote you, and the less you stand to earn back in general. The “votes” are simply numbers in storage - you never touch them as a user. All the complexity is kept in the contract, and you can see who ranks where and why at a glance, safe(r) in the knowledge that those who rank highest are providing the most economic value to the community.

Here, we have programmed SNT to create the most radical market we could imagine, while making sure to protect against abuse from the rich. The richer the actor, the more protection - and community benefit - is implied, simply by using the token. Perhaps this seems trivial now, but when you realise that this curve is but one “module” that we can plug into one of many tokens on Ethereum, which is one of many blockchains; the rate and scale at which things are getting weird boggles the mind.

The synchronicity I mentioned occurred when Billy Rennekamp submitted https://clovers.network to Discover just before it’s launch at #BerlinBlockchainWeek. Clovers uses bonded curves in an entirely different way than Discover does, and yet here they are; a game of curves and proof-of-search appearing in a store aimed at helping you search the most useful and valuable DApps. Both spring from the underlying realisation that we can make money respond to the markets it exists on, such that it is directed to find information we collectively deem to be scarce, and therefore more valuable.

Billy and his team have used a bonded curve to create an internal, automated economy where you can buy and sell “clovers” you have found (the main aim being to find symmetrical layouts on a board, which are more valuable because they’re rare). The unique design allows you to hold your own Clover tokens (unlike the votes in Discover), and sell these to exit back into ETH.

The two implementations, and our goals in creating two new DApps, are very different and yet, precisely because of this, they show (in production!) just how unexplored the possible designs of programmable money really are and, hopefully, give you some bright ideas about what to #buidl next.

Welcome to the wild west of incentive design: it gets strange, but even Simon says he's excited, so grab a curve and begin bending your mind around all its possibilities.

P.S.

One extra note on markets themselves. To me, markets are interesting primarily because they facilitate inter-temporal trades. The value I produced today can be represented by an abstraction such that I don't need to wait for you to produce some value tomorrow in order to trade. Money expresses value in a more stable fashion than perishable goods or services, thus it is the medium we use to make markets into more efficient mechanisms for time-travelling incentive alignment.

What happens, though, when the narrative machinery is composed in a language which can reflect - even rudimentally - upon that machinery's role in which incentives are aligned throughout time? Perhaps we are inter-temporal beings already, and now we just need to get good at it.